The Atlantic Operation of the Bismarck-Prinz Eugen Battlegroup

Content

1. Preparations.

-

Directives from the Seekriegsleitung, Group Nord and West.

Operational Order of the Fleet.

3. The Voyage of the "Prinz Eugen" 24 May to 1 June.

4.The Countermeasures of the English Naval Warfare.

5. The Fate of the Escort Ships.

6. Operational Conclusion.

7. Closing Words.

2. Execution of the Operation.

The participation of the "Gneisenau" in the operation, as planned in the original directive of the Seekriegsleitung, had to be cancelled because her damage could not be repaired at the shipyard in Brest by the scheduled date. The start of the operation, for which the Seekriegsleitung had planned the new moon period in April (new moon 26 April), was delayed until the second half of May due to a coupling damage reported on 24 April on "Prinz Eugen", and later due to the failure of the portside boat crane on "Bismarck" as a result of coupling damage in the boom extension winch. This delay had the disadvantage that darkness no longer occurred in the high northern latitudes, making it more difficult to break through unnoticed and shake off any possible surveillance ship.

On 16 May, the Fleet command reported the battlegroup ready for "Rheinübung" as of 18 May, 0000 hours.

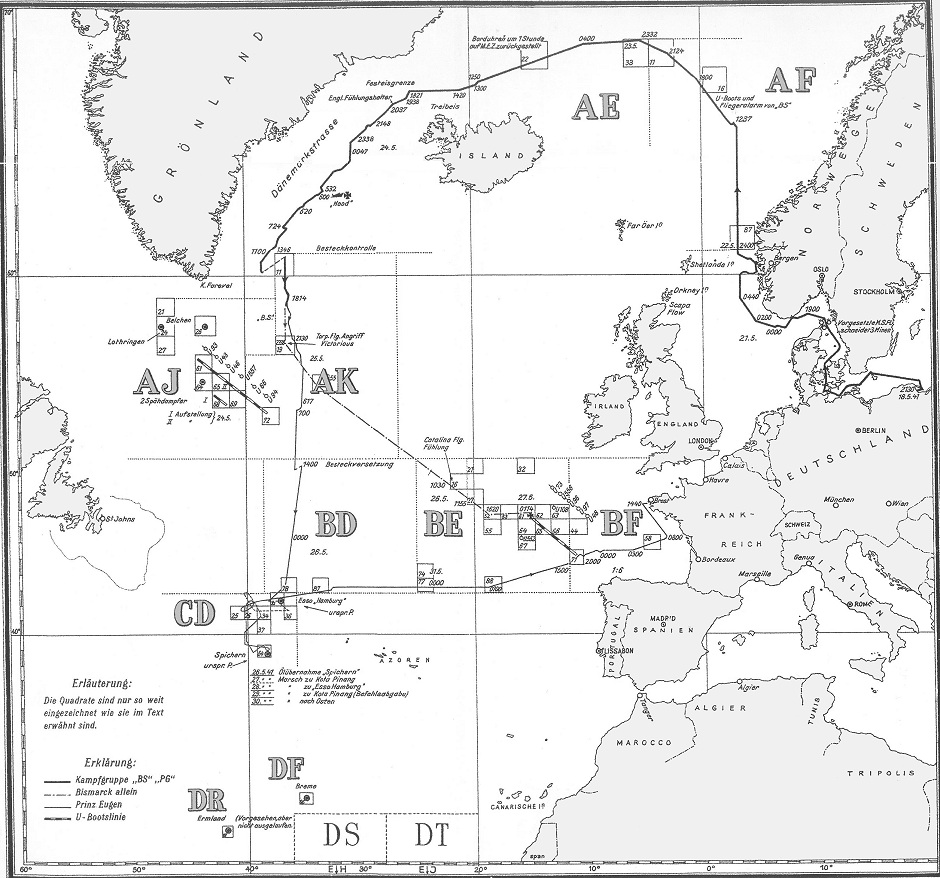

On 17 and 18 May, respectively, the two motor ships "Gonzenheim" and "Kota Pinang" (each 14 knots), which were intended as reconnaissance ships, left La Pallice for their stations. Likewise, the "Weißenburg" and "Heide", which were intended as tankers in the North Sea, as well as the escort tankers "Belchen", "Lothringen", "Esso Hamburg" and "Friedrich Breme" intended for the Atlantic, and the supply ship "Spichern" also began their march to their waiting positions.

On 17 May, Group North issued the codeword according to which the battlegroup was to enter the Great Belt on 19 May at nightfall.

In a commander's meeting on "Bismarck" on the morning of 18 May, the Fleet Commander announced his intention not to stop in the Korsfjord near Bergen if the weather was favorable, but to head straight for the North Sea and refuel there from the tanker "Weißenburg". From there, the breakthrough through the Denmark Strait was to be attempted at high speed, which was to be maintained even with the visibility reduced by the expected freezing fog. It would then be time to navigate by radar. If cruisers or auxiliary cruisers were to stand in the way, they were to be engaged, otherwise conserve ships for long term endurance. In such a battle with light forces, "Prinz Eugen" should only use her torpedos on orders from the Fleet. The ships march separately to Arkona and meet there at 1100 hours on 19 May.

The Fleet Commander therefore is clearly in favour of the Denmark Strait, as he did in his aforementioned operational order dated 22 April, while Group North had recommended the Iceland-Faroe passage. The following reasons were decisive for the Group:

-

a) The Denmark Strait is expected to be narrow and, in extent, ice-free.

b) The enemy is expected to guard this gap, which prevents anyone from passing unseen.

c) It is easier to keep in touch after passing in the north than in the south, since the southern guards can be called upon to keep in touch; not the other way round.

d) Time and fuel savings can be gained if the southern breakthrough is attempted immediately after leaving the Norwegian coast, instead of heading north on the outer arc, which may require refilling with oil before attempting the breakthrough.

e) Gain a head start on Scapa forces in the southern passage more quickly once they are aware of the breakthrough.

19 May.

At 1125 hours on 19 May, the formation with the destroyers "Friedrich Eckoldt" and "Z23" as well as mine barrage breakers assembled at Arkona and continued the march to the Great Belt on the Green and Red routes. At 2234 hours the destroyer "Hans Lody" joined the group at point Red 05.

By order of the "Commander of Baltic Sea Security" [BSO], all commercial traffic through the Great Belt and Kattegat would be halted for the night of 19/20 May and for the following morning to keep the Rhine exercise secret.

20 May.

On the morning of 20 May, the Swedish aircraft and mine cruiser "Gotland" was sailing close to the formation under clear visibility off the Swedish coast. The Fleet Command in the radio telegram report expresses the assumption that the formation has been reported in this way.

A minesweeping flotilla moves forward in front of the Skagerrak barrier, cuts three mines, the battlegroup is withdrawn, sets off again and passes the barrier at 1600 hours. The march then continued at 17 knots, using zigzag turns and anti-submarine protection by the three boats of the 6th Destroyer Flotilla, and as darkness fell the Kristiansand-South barrier gap was passed.

21 May.

The night march passes without further incident. Shortly after 0700 hours on 21 May, four aircraft came into view in the west. The nationality of the machines could not be determined. It must be considered that they were British aircraft. Shortly before, following the decryption by the Intelligence Service, English aircraft were instructed to look out for 2 battleships and 3 destroyers that had been sighted on a northerly course. It is uncertain whether the aircraft mentioned above are connected with this order. What is certain is that the departure of the Bismarck group through the Great Belt/Kattegat was observed by agents of the enemy observation and intelligence service, which is known to work very well, and passed on to the enemy via the intelligence center at the British naval attaché in Stockholm. In any case, the decryption provided the first sign that the departure of the battlegroup had been noticed by the enemy.

At 0900 hours the formation enters the Korsfjord, "Bismarck" anchors in the Grimstadfjord at the entrance to the Fjösanger Fjord, while "Prinz Eugen" anchors further north in the Kalvenes Bay and fully refuels from the tanker "Wollin". The camouflage paintwork used up to this point is painted over in grey.

The reasons which led the Fleet Commander to enter the Korsfjord contrary to his original intention are not known.

At 2000 hours the formation regroups at Kalvenes Bay and leaves the archipelago through the Hjelte Fjord at around 2200 hours.

22 May.

The three escorting destroyers were released to Trondheim at 0510 hours on 22 May off Kristiansund-Nord. The Fleet Commander did not give them any information about his further intentions. From the lack of such a report, despite verbal instructions, Group North concluded in its war diary that the Fleet Commander had no firm intentions at that time, but wanted to make them dependent on the weather conditions and other circumstances. It is more likely, however, that the Fleet Commander did not consider a new report necessary, since he stuck to his intention, as stated in his operational order, to attempt a breakthrough through the Denmark Strait.

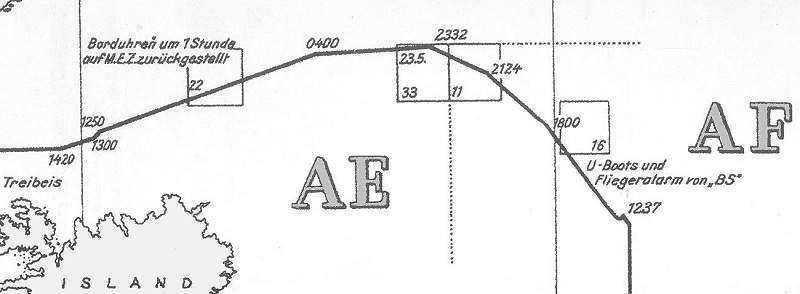

At noon, (the weather was overcast, partly hazy with winds SSW 4) after regrouping the formation was at 65º 53' North and 3º 38' East, i.e. around 200 nautical miles off the Norwegian coast in the Iceland-Norway line. The Fleet Commander signaled his intention: starting at 1200 hours advance through quadrants AF 1675, 1155, AE 3313, 2257. If the current favorable weather conditions change, march to "Weißenburg" (refuel).

This means: Proceeding as fas as 69º North, march towards the Denmark Strait in order to take advantage of the currently favourable weather conditions. The march was continued at 24 knots; for the following morning at 0400 hours, steam was ordered for 27 knots and transition from battle cruising condition 2 to 1.

At 1237 hours, "Bismarck" gives a submarine and air raid alarm, the battlegroup turns to port and travels in zigzag courses for half an hour; at 1307 hours, the previous course is resumed.

The weather, the most important factor for the breakthrough, is developing extremely favourably and, according to the meteorologist aboard the "Prinz Eugen", offers the prospect of holding steady until reaching the southern tip of Greenland. With light south-westerly winds, it is hazy and rainy, with visibility limited to 300-400 meters, so that the flagship can no longer be seen from the cruiser behind and only navigates by following its wake. In the bright night, the speed can be maintained at 24 knots.

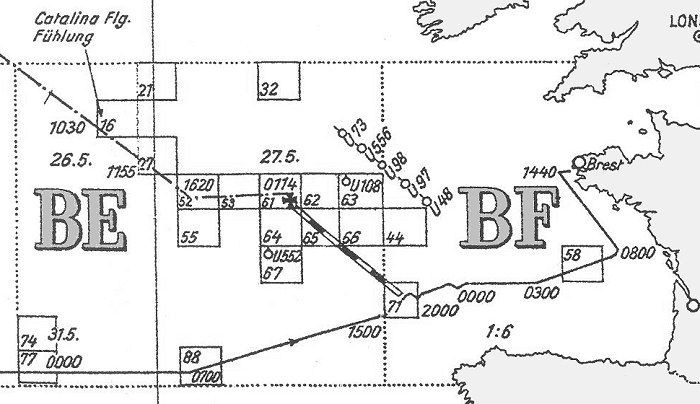

For the sake of clarity, the attached map contains only the first two digits of the quadrant numbers.

For the sake of clarity, the attached map contains only the first two digits of the quadrant numbers.

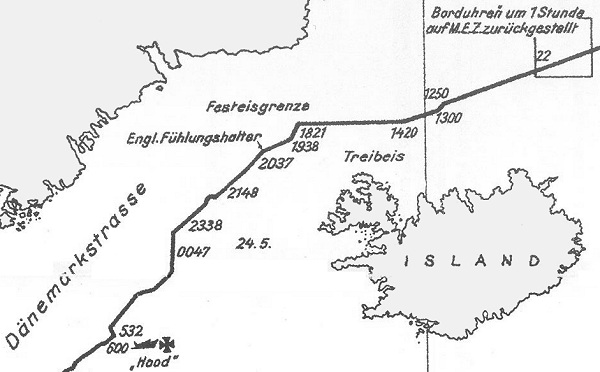

23 May.

The march continued under the same conditions on 23 May, the plotted position at noon was 67º 28' North, 19º 28' West; i.e. before the entrance to the Denmark Strait, about 75 nautical miles north of Iceland's northern coast.

At 1300 hours the ship's clocks are set back one hour to Central European Time.

The enemy situation, as it must have appeared to the Fleet Commander on the basis of the news transmitted from home as he entered the critical phase of the operation, was as follows:

The enemy had learned of the formation's departure, as indicated by the order from an English ground radio station on 21 May at 0620 hours to look out for 2 battleships and 3 destroyers on a northerly course. It is not known whether this report refers to the journey through the Belt and Kattegat (agent) or the march along the Norwegian coast (aircraft). Group North assumes the former and has radioed the Fleet [see BS & PG War Diaries 2038 hours, 21 May]:

-

"Hold likely basis for sighting report from Great Belt agent service."

Any operational impact of these observations on the British naval forces cannot be determined by the intelligence service from radio communications. Group North therefore transmitted to the Fleet on 22 May in the morning [see Bismarck War Diary 0934 hours, 22 May]:

-

"No unusual peculiarities in air radio traffic; no operational radio traffic, no resulting effect of the departure of the Fleet or of the English order to search for the battleships can be detected.

Only increased air reconnaissance in the north-eastern sector."

-

Occupation of Scapa Flow according to visual observation of 22 May 1941 is same as that captured with aerial photo surveillance on 20 May.

Aerial surveillance today not possible due to weather (4 battleships, one of them possibly an aircraft carrier, apparently 6 light cruisers, several destroyers)

-

"Thus no changes relative to 21 May and advance through narrows of Norway not detected."

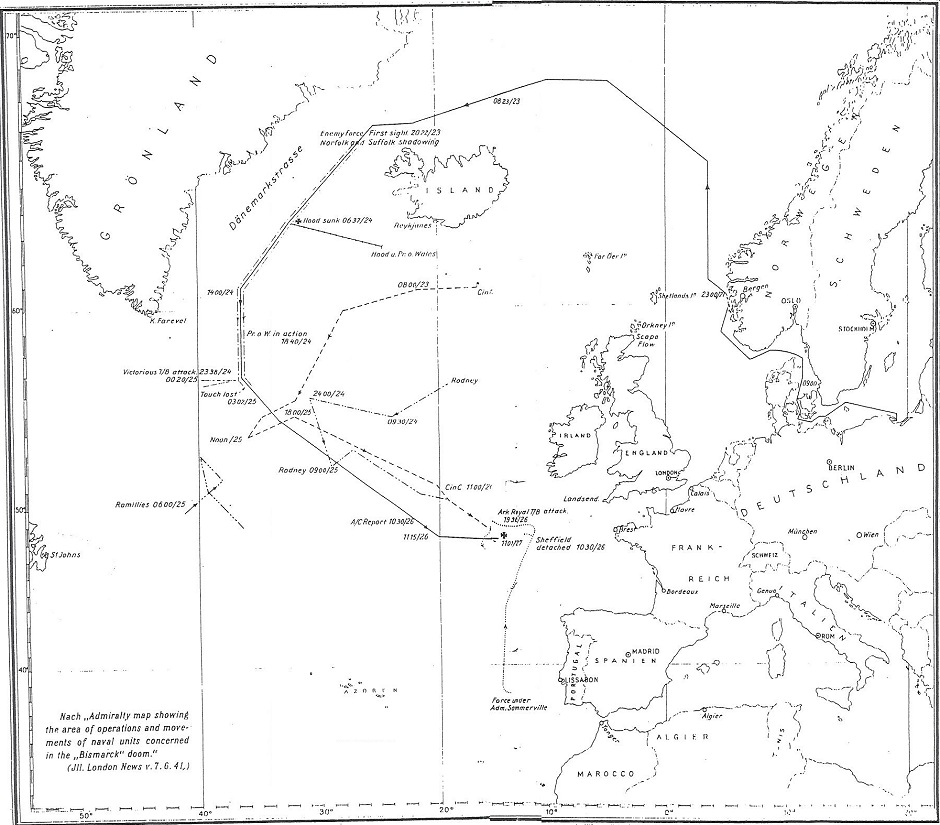

Subsequent findings lead us to assume with certainty that the visual reconnaissance of 22 May, according to which four battleships were supposed to have been in Scapa Flow, was incorrect. By linking the position of the English ships on 24 May (see attached English map), it is clear that the bulk of the Home Fleet must have left Scapa early on 22 May, probably immediately after receiving the report from the aircraft that had searched the fjords near Bergen the previous night, found them empty and thus confirmed the departure of the German battlegroup. The limited reliability of visual reconnaissance from the air in adverse weather conditions was demonstrated on 24 May. In the afternoon, after the battle with Hood-Prince of Wales, the "Air Commander North" reported:

-

"Visual reconnaissance only through a hole in the clouds, but berths were seen: 3 battleships, including probably "Hood".

It could not be clearly determined whether there was also an aircraft carrier.

Also 3 cruisers, probably light ones."

-

"Scapa Flow today, 24 May, shows occupancy not as previously reported by visual observation: 3 battleships, 3 cruisers, but only 2, presumably light cruisers and artillery training ships."

-

"After a detailed analysis of the aerial photographs of Scapa on 24 May, only one light cruiser, 6 destroyers and a few smaller warships and merchant ships could be identified."

The reconnaissance of the Denmark Strait by German aircraft was incomplete due to the small number of aircraft available for this task and the unfavourable flight and visibility conditions. The last report was on 19 May, when a FW 200 had identified the drift ice border north of Iceland at a distance of about 70 to 80 nautical miles. The flight had to be aborted 50 nautical miles north-west of Cape North due to low-lying fog; drifting ice was still observed there.

There are no new reports of patrol vessels in the Denmark Strait, but based on experience from previous operations, surveillance by auxiliary cruisers and cruisers was to be expected.

The weather forecast transmitted to the Fleet on the afternoon of 23 May confirmed the bad weather conditions favourable for the breakthrough and stated [see Bismarck War Diary 1403 hours, 23 May]:

-

"Weather for 24 May. Route north of Iceland winds SE to E at Force 6-8, mostly overcast, rain, moderate to poor visibility.

Low pressure system 980 milibars expected east of Iceland.

Warm air flow to Denmark Strait and area south of Iceland."

At 1922 hours, the alarm was raised again by "Bismarck". On the "Prinz Eugen" standing behind, a shadow was seen at a distance of 13,000 meters in a 340º direction. It was identified as an auxiliary cruiser and immediately disappeared into the mist. "Bismarck" fires about 5 salvos and signals "JD" to the formation. "Prinz Eugen" could not open fire because the target had disappeared again.

The radio reconnaissance intercepts the enemy’s first contact signal with:

-

"2032 1 battleship, 1 cruiser at 330º, 6 nautical miles off, ..... course 240º."

The Fleet Commander reports with a short signal:

-

"AD 29 a heavy cruiser."

Soon afterwards, it became clear from enemy radio traffic that a second contact had been made; these were the two heavy cruisers "Norfolk" (Capt. A. J. L. Phillips), flagship of Rear Admiral W. F. Wake-Walker, and "Suffolk" (Capt. R. M. Ellis), which according to the announcement by the British Admiralty, had been sent to guard the Denmark Strait following the air report of the disappearance of the German battlegroup from the Bergen Fjords.

The intelligence service aboard "Prinz Eugen" believed that it could also identify the "King George" as the contact ship from the radio traffic. This was a mistake, but if the Fleet command was of this opinion, it might have later influenced the Fleet Commander's decisions after the battle with "Hood" and "Prince of Wales" regarding the choice of destination port and the route there.

The two British cruisers maintained constant contact with the German formation throughout the night. All attempts by the Fleet to evade them by increasing speed to 30 knots and by creating fog were unsuccessful; even the increasingly poor visibility and snowfall were no hindrance to the English; every change in course and speed was detected by them in no time and reported by radio telegram, as was deciphered by the radio reconnaissance on board and at home. The Fleet Commander concluded from this (see radio telegram of 25 May, 0401 to 0443 hours) that the English had a radar device that worked perfectly over long distances, a realization that was of great importance for the current operation and for the future conduct of the war.

According to the findings of the Naval Intellitence service [Skl./Chef MND], the ability to keep in touch in poor visibility and at great distances does not indicate so clearly the presence of radar devices on the English side as the Fleet Commander assumes. Well-functioning listening devices [hydrophones] are also a possibility, for which the best conditions exist here in the cold water zone of the Denmark Strait. It is also still an open question whether the enemy did not gain contact with the battlegroup by intercepting the German radar pulses or the VHF device.

24 May.

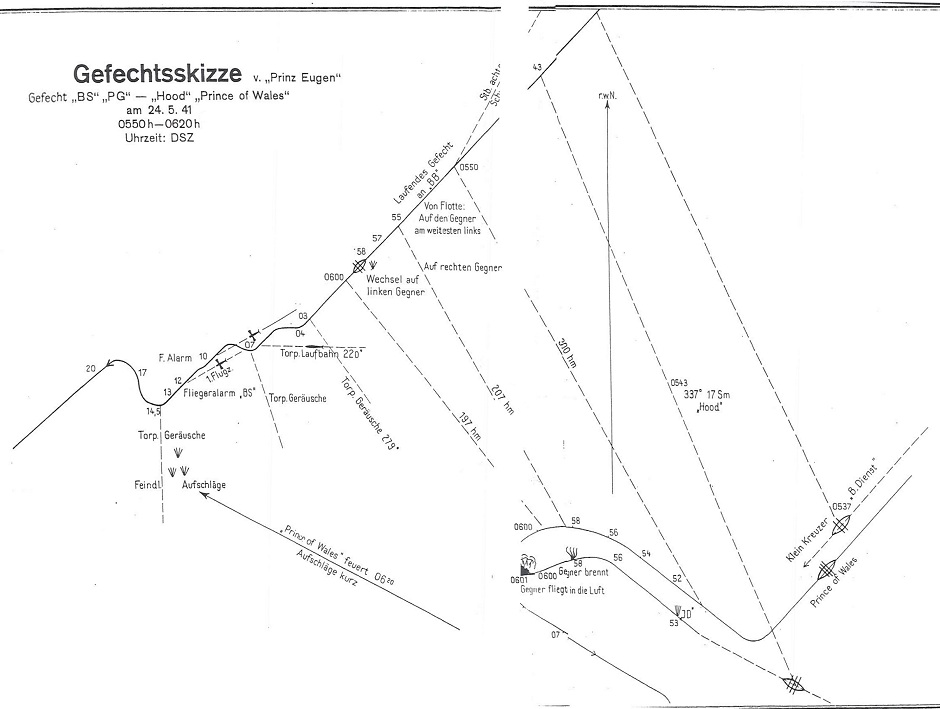

At 0545 hours, the intelligence service discovered two more units on the port side, which soon became visible to the eye on the horizon abeam to port due to rapidly growing plumes of smoke. It was Rear Admiral Holland's battlegroup, consisting of his flagship the "Hood" (Capt. R. Kerr) and the new battleship "Prince of Wales" (Capt. J. C. Leach), which the German side initially referred to as "King George V". They approached the German formation at full speed in a very acute angle and opened fire from around 29,000 meters at 0553 hours. This was returned two minutes later by the German side, with both ships combining fire on "Hood". Both ships found their target after the first salvo, the second salvo from "Prinz Eugen" caused a rapidly spreading fire at the height of the aft mast of "Hood", apparently due to hits in the aircraft hangar or fuel depot. After the 6th salvo, "Prinz Eugen" following a signal from the Fleet shifted to the target further to the left, the "Prince of Wales", and observed 2 hits there with a small fire (0559 hours).

At 0601 hours, the "Hood" is blown apart by an extraordinarily strong detonation after being hit by the "Bismarck". A high column of metal debris rises up, a heavy, black cloud of smoke envelops the ship, which sinks rapidly by the stern while twisting about 180º.

When the detonation cloud had cleared, there was no sign of the "Hood", the world's largest battleship to date with its more than 42,000 tons. An armor piercing shell from the "Bismarck" had penetrated the side armor of the "Hood" and exploded in the aft ammunition chamber of the English battlecruiser. The same fate that had befallen the British battlecruisers "Indefatigable", "Queen Mary" and "Invincible" in the Battle of Skagerrak [i.e. Jutland] and the English flagship "Good Hope" at Coronel (ignition of the ship's own ammunition inside due to an armor-piercing hit) also befell the "Hood". The design changes and modifications undertaken on the basis of experience from the World War had proven inadequate for this ship.

Between 0603 and 0614 hours, the "Prinz Eugen" had to avoid three torpedo paths; she managed to outmaneuver them, but this meant that the cruiser was deprived of the only opportunity during the battle to launch her own torpedoes against "Prince of Wales", which was at the limit of its range and now showing its full broadside. The origin of the English torpedoes cannot be clearly determined, as the "Prinz Eugen" war diary states, especially since there were aircraft nearby. Given the position and distance, they could only have been shots from "Hood", whose torpedoes had the greatest range. The sound location of the listening room was certain, and the second and third bubble paths were observed by the commander outside the command post after they passed.

The "Prince of Wales", which had sailed next to her flagship in a blunt starboard formation, turned around the wreck and debris field after the sinking of the "Hood" on a southerly course, evaded the concentrated fire of the two German ships by creating fog and black smoke and broke off the fight. At 0621 the Englishman fired a few more salvos, but they were considerably short (the distance was over 35,000 meters). The shawdowing ships "Norfolk" and "Suffolk" remained in their rearward positions throughout the entire battle and did not appear.

The ammunition consumption on the German side was:

-

"Bismarck" . . . . . . . . . 93 rounds of heavy artillery

"Prinz Eugen" . . . . . . 179 rounds of heavy artillery

The "Prinz Eugen" was fortunate in the battle, she was not hit, although heavy artillery strikes were observed on all sides in the immediate vicinity of the ship, any one of which could have been fatal to the cruiser given its weak armor. Contrary to the prevailing tactical principles, neither the Fleet Commander nor the Commander had the ship (which must be classified in the light forces category due to its armor strength) moved out to leeward at the start of the battle, but instead kept it in line, a risk that in this case was justified by the success. The deviation from our tactical principles at the start of the battle was probably caused by the fact that the British ships approaching were initially referred to as heavy cruisers, and this was then maintained later when the enemy was recognized as a battleship formation. This forced the latter to distribute fire. The hits scored by "Prinz Eugen" may have been of great importance. Group North Command comments on this: "One must not think in a schematic way and must accept risks. Dangers (as is the case here) do not always mean losses or destruction."

"Bismarck" had received two heavy hits: one in Section XIII-XIV, causing failure of electric plant No. 4, port boiler room No. 2 is taking on water that can be held back. Second hit was in the forecastle Section XX-XXI, projectile entering portside, exiting starboard above armored deck, oil cells hit. Third hit through a boat of no consequence. 5 lightly wounded. Maximum speed was reduced to 28 knots. Water in the forecastle. The battle report from the Fleet Commander, which he sent to Group North at 0632 hours:

-

"Battlecruiser, probably Hood, sunk. Another battleship, King George or Renown, damaged turned away. Two heavy cruisers keep up surveillance."

The repetition of the battle report at 0801 hours was not received at home until 1340 hours; it contains the following remark:

-

Denmark Strait 50 nautical miles (i.e. width of the ice-free strip 50 nautical miles), drifting mines. Enemy radar devices.

-

Intention to enter St. Nazaire. "Prinz Eugen" cruiser war.

Both groups take the necessary measures to recover the "Bismarck". [Group] North (in the event that the Fleet Commander decides to retreat to the Norwegian coast, contrary to the previously reported intention) sends the 6th Destroyer Flotilla to Bergen, requests the Commander-in-Chief of U-boats to have submarines on standby in the Faroe Islands-Shetlands-Norway area, and Air Fleet 5 to have air combat and reconnaissance forces ready, as well as reconnaissance of Scapa, the Firth of Forth, the Clyde and Loch Ewe. Group West initiates the necessary protection and security measures for St. Nazaire and expects the arrival there on the morning of 27 May.

The considerations that led the Fleet Commander to choose St. Nazaire are unknown to us after the loss of the war diary on the "Bismarck"; he also did not send any information about this to the commander of "Prinz Eugen".

To reach their own base, four routes were available:

-

1. The one chosen by the Fleet Commander to St. Nazaire,

2. The shortest to the Norwegian coast near Bergen,

3. To Trondheim south past Iceland,

4. To Trondheim through the Denmark Strait.

-

1. To St. Nazaire directly 1,700 nm, if heading out into the Atlantic at least 2,000 nm,

2. To Bergen 1,150 nm,

3. To Trondheim south of Iceland 1,300 sm,

4. To Trondheim through the Denmark Strait 1,400 nm.

2. The route to Bergen was the shortest of all and would have led the fastest into the area of our own air and coastal defences. However, it passed between the Faroe Islands and the Shetlands and thus close to the enemy air and sea bases. Moreover, if the Home Fleet was still there or nearby, as seemed possible according to the latest reconnaissance results from Scapa, it would have led directly towards them. Choosing this route was therefore out of the question.

3. The route to Trondheim south of Iceland (150 nautical miles longer than the route to Bergen) had similar disadvantages.

4. The route through the Denmark Strait was only slightly longer than the one south of Iceland. However, it offered the great advantage that it led back into the area of very poor visibility near the ice limit, and even if this did not rule out contact between ships, based on the experience on the outward journey, it did significantly reduce the danger from the air. The North Sea offered space for maneuvering and disengaging; own air support could cover the ship halfway between Iceland and Norway. Finally, this route most effectively avoided the bulk of the English fleet, should it advance towards the battlefield upon receiving news of the battle with the Hood.

The route through the Denmark Strait would therefore have been the best.

We can only guess what prompted the Fleet Commander to choose the route to St. Nazaire. As mentioned above, the "Prinz Eugen" believed that a battleship of the "King George V" class was also located with the two shadowing ships "Norfolk" and "Sufflok". If that was the case, then the "Bismarck" would have been heavily outnumbered by the "Prince of Wales", which was probably not badly damaged, and the two heavy cruisers that were keeping in touch when they turned around. In reality, the "King George V" was at this time, as can be seen from the English publications (see attached Admiralty map), more than 300 nautical miles southeast of the "Bismarck's" position and would not have been able to catch up.

Then it emerges from the Fleet's radio messages and the war diary of the "Prinz Eugen" that both ships were very much impressed by the completely unexpected discovery of very well-functioning radar devices on the English ships, which made it possible to keep contact even in fog and at great distances. This, combined with the very incomplete knowledge of the location of the heavy English ships, probably made the retreat through the Denmark Strait seem more difficult to the Fleet command than it actually turned out to be based on later experiences, which came on 25 May when contact was lost.

However, the decisive factor for the Fleet Commander (and this can be assumed with certainty given Admiral Lütjens' personality and his sense of duty) was not so much the question of which port the ship could reach most safely, but rather his task, which he must have put before everything else with the persistence that was typical of his nature. This task was to deploy the battlegroup against enemy supplies in the Atlantic. For Admiral Lütjens, there was certainly no alternative: the ship naturally went to St. Nazaire in order to be deployed for Atlantic operations as soon as possible or even while still on the way there. Only if this port had been inaccessible or if the ship had been so damaged that it could not be repaired in St. Nazaire would Admiral Lütjens probably have considered returning.

Meanwhile, a collision mat had been raised over the shell holes in the forecastle on "Bismarck", but this could not prevent oil from seeping through from the damaged fuel cells. A broad, widely visible oil trail formed in the ship's wake, which could have been very disadvantageous to detection by aircraft. To check this oil trail in the weather, which was now becoming foggy and rainy again towards midday, "Prinz Eugen" fell back and, after reporting its observations, resumed position in front of "Bismarck".

Noon position 60º 50' North, 37º 50' West, [wind] East 3, Sea state 3.

At 1300 hours the battlegroup had to reduce its speed to 24 knots in order to allow for sealing work in the forecastle of the "Bismarck".

At this time, the radio messages from the Fleet command about the battle with "Hood"-"Prince of Wales" and the intention to go to St. Nazaire were received at home for the first time. At 1400 hours, the Fleet Commander reported:

-

"King George” with cruiser keeping surveillance. Intention: If no fight ensues, disengage during night."

Rain squalls with poor visibility made an unnoticed separation of the two German ships by the enemy seem successful. At 1420 hours, "Prinz Eugen" received the semaphore signal:

-

"Intend to shake stalker as follows: During rain squall, the "Bismarck" will change course West, "Prinz Eugen" will maintain course and speed until he is forced to change position (course) or 3 hours after departure of "Bismarck".

Subsequently, [Prinz Eugen] is released to take on oil from "Belchen" or "Lothringen".

Afterwards, pursue independent cruiser war [patrol]; Implementation upon cue word, "Hood"."

"Bismarck" turned to starboard and disappeared from sight, but reappeared at 1559 hours and made a semaphore signal:

-

"Bismarck" into staggered formation again, there is a cruiser on the starboard side.

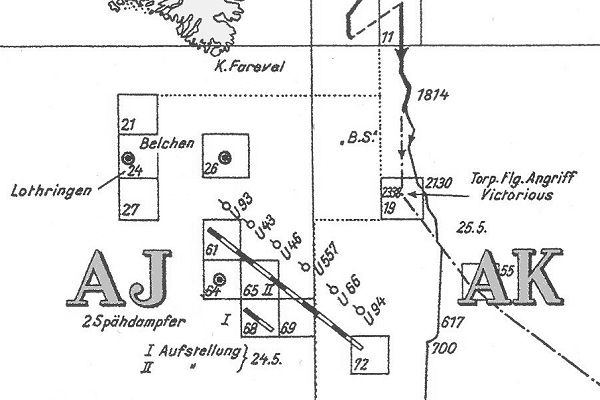

Regarding the further intentions of the Fleet Commander, a radio telegram from 1442 hours provides information with the instruction to the Commander-in-Chief of U-boats:

-

"Boats in the West assemble in quadrant AJ 68; tomorrow at dawn “Bismarck” intends to draw the stalking heavy units coming from the North through quadrant AJ 68."

The Commander-in-Chief of U-boats ordered the boats to form an outpost strip from AJ 6815 to AJ 6895; positions were to be reached by 0600 hours on 25 May, depth 10 nautical miles. Attacks were only permitted against enemy warships. At the same time, U93 and U73 were positioned in AJ 6550 and 6950. As a precaution, the Commander-in-Chief of U-boats positioned U98 and 97, returning from operations, and the departing U48, west of the Bay of Biscay (in Quadrants BE 64, 65, 66), U138 was positioned for attack in BG 4420.

By radio telegram 1711, Group West informed the Fleet Command that the submarines would be in the desired quadrants the next morning. At 1842 hours, Group [West] reported that preparations were being made in St. Nazaire and Brest, that it agreed with the release of the "Prinz Eugen", and that it considered it expedient for the "Bismarck" to wait longer in a remote sea area if the release was successful.

This last instruction is entirely in line with the opinion of the Seekriegsleitung, which hopes that a longer deployment of the "Bismarck" into the Atlantic will lead to a decline in the hunt that the British are now conducting with all their forces. At the moment, it must be assumed with certainty that all Scapa ships and the aircraft carrier "Victorious" have set sail for operations against "Bismarck", probably also from Gibraltar the Force H, which has been outside Gibraltar in the eastern Atlantic since the night of 23/24 May, and possibly also some of the battleships escorting the Halifax-England route. The report from the air reconnaissance of Scapa, which arrived that afternoon, according to which visual reconnaissance had identified 3 battleships and 3 cruisers there, is considered by the Seekriegsleitung to be implausible from the outset, which is also confirmed by subsequent image analysis.

It is therefore all the more surprising and worrying, that after the Fleet Commander reported at 1914 hours a brief, inconclusive battle with "King George" (in reality "Prince of Wales"), he sent the following message at 2056 hours (received at 2132 hours):

-

"Shaking off stalker impossible because of enemy radar. Due to fuel [shortage] will proceed directly to St. Nazaire."

A calculation of oil consumption made shortly before by Group West had shown:

| Stock on 18 May, 0000 hours | 7,700 m3 |

| Consumption from 18 to 22 May each 300 m3 = 1,200 m3 | |

| Consumption from 22 to 23 May at 21 knots = 450 m3 | |

| Consumption from 23 to 24 May at 28 knots = 960 m3 | |

| 2,610 m3 | |

| Stock on 24 May, 0000 hours | 5100 m3 rounded |

From this it was concluded that, until the arrival, even in the event of further combat actions and the resulting stay at sea, there was no need for concern, unless heavy oil losses had occurred as a result of the hits.

This concern was now confirmed, the Fleet Commander was deprived of the freedom to decide on the route to be taken due to the lack of fuel. This also eliminated the possibility of drawing the following heavy ships over the U-boats stationed in quadrant AJ 68. The change in intentions led to a change in the orders of the Commander-in-Chief of U-boats to his western boats, which were now stationed in an outpost strip from AJ 6115 to AK 7215 (U93, 43, 46, 557, 66, 94). U556 was stationed as a reconnaissance boat in BE 5260.

For the sake of clarity, the attached map contains only the first two digits of the quadrant numbers.

For the sake of clarity, the attached map contains only the first two digits of the quadrant numbers.

In the following description of the events up to the final battle, since only short radio messages are available from the German side due to the loss of the Fleet's war diary, reference is made to the official English account and those in the press, insofar as they are credible and in accordance with our own observations, as well as to the account in Nauticus 1942, which, like this report, was compiled by the Navy's War Science Department.

At 2338 hours the Fleet Commander reported:

-

"Aircraft attack quadrant AK 19."

The war diary of the Seekriegsleitung concludes 24 May with the following comment:

-

"At the end of the eventful day, the proud joy of sinking the "Hood" and the overall assessment of the situation are combined with the concern as to whether it will be possible to detach the "Bismarck" from the enemy and bring it safely to the French west coast."

Shortly after midnight, the second wave of "Victorious" aircraft hit the "Bismarck" and, out of 18 torpedoes dropped (the number was given by a rescued Matrosengefreiter), scored one hit on the starboard side at the height of Sections VIII-X. The Fleet Commander reported this attack at 0028 hours, adding that the effect of the torpedo hit was insignificant (it probably hit the armor) and that further attacks were expected. Location quadrant AK 19.

According to survivors, 5 aircraft were shot down by anti-aircraft guns, one each by heavy artillery and secondary artillery. As announced to the crew via the loudspeaker system, only one of the 27 aircraft is said to have returned to the carrier. The source of this information is unknown, probably a decryption by the ship's intelligence service.

As a result of the increased speed during this attack ("Bismarck" made 27 knots), the zigzag course and the torpedo evasion maneuvers, the sealing of the forecastle with collision mats did not hold up. The collision mats tore and resulted in water entering again, causing the forecastle to sink deeper. In addition, the cracks in the sealed bulkhead between electric plant No. 4 and port boiler room No. 2 are said to have grown larger as a result of the vibrations caused by the ship's own heavy defensive fire, so that the port boiler room No 2, which was already flooded, could no longer be held and had to be abandoned.

In response to the changed situation, which makes a return of the German ships to the north unlikely, Group West moves the two reconnaissance ships "Gonzenheim" and "Kota Pinang" to CD 23 and CD 26 respectively, and plans to position 5 U-boats in the eastern half of BE up to BF (in front of the entrance to Biscay); the West U-boats, i.e. those that were to assemble in AJ 68, receive orders to advance eastwards.

In the English contact reports, which were evidently based on detection rather than sight, a certain confusion arose after the separation of the "Bismarck" and "Prinz Eugen". Up to 2234 hours, according to the intelligence report, contact was reported with a battleship and a heavy cruiser, but since then only with one battleship, so that Group West gets the impression that the separation of the "Prinz Eugen" only took place around this time. At 0213 hours, contact with only a battleship was reported at 56º 49' North and 34º 08' West, with enemy [Bismarck] bearing 195º, 11 nautical miles away.

From this point on, no more contact reports were received; the enemy had lost contact.

This impression also prevailed at the Seekriegsleitung and Group West, which communicated this perception to the Fleet as well. They were therefore surprised when, at 0908 hours a radio telegram from the Fleet arrived, timestamped 0700, with the following wording:

-

"0700 hours quadrant AK 55. One battleship, 2 heavy cruisers are continuing surveillance."

At 0942 hours, Group West received a radio telegram from the Fleet:

-

Time-segments 0401, 0417, 0428, 0443 (transmitted after 0900).

Possession of radar equipment by opponent, effective range at least 350 hectometers [35,000 meters], adversely affects to the highest degree the Operations in the Atlantic. Ships were located [position fix] in the Strait of Denmark in dense fog and continuously tracked [locked on or not released again]. Disengagement failed even in favorable weather conditions. Oil replenishment is generally no longer possible, if disengagement of opponent cannot be accomplished with higher speed. Running battle between 208 and 180 hectometers [20,800 and 18,000 meters]. Opponent “Hood” concentrates fire on “Bismarck”. After 5 minutes, “Hood” is destroyed by an explosion; thereafter, change of target to “King George” who then turns away in black smoke caused by definitively observed hits. He remains out of sight for several hours. Own munition expenditure: 93 rounds. Later, “King George” took on the fight only at extreme distances. “Bismarck” received two hits from “King George”; of those one hit below the side armor belt at Section XIII to XIV. Hit in Section XX to XXI impaired speed and caused a 1º bow burying forward and destruction of oil cells. Release of “Prinz Eugen” was possible by engagement of battleship [BS] with cruisers and battleship during fog. Own EM-2 Radar instrument prone to failures, especially during firing.

In reality, however, the British lost contact very soon after the aircraft attacks. This is not only evident from the consistent reports of the British Admiralty and press, but also convincingly from the analysis of the British ships' movements according to the Admiralty map mentioned above. In particular, the courses of the flagship group with "King George V" and "Victorious", and that of the "Rodney", suggest that they no longer received any contact signals shortly after midnight on 24-25 May. While up to that point the courses of all ships clearly indicate a target-oriented effort to converge on the "Bismarck", they suddenly diverge widely: "King George V" advances to the west, "Rodney" turns to the SSE. They adopted search courses until the afternoon of 25 May, when both settled on a course almost parallel to the "Bismarck" at a distance of about 100 nautical miles and continued to follow this course undeterred, despite the absence of any contact either by water or by air.

What could have caused the British fleet commander to stubbornly stick blindly to this course?

It is mentioned above that the German fleet command reported by radio telegram at 0700 hours that contact with the enemy was still maintained (although it had actually been lost for more than four hours). Furthermore, a very long radio message was sent and received by Group West from 0912 hours to 0918 hours about the situation and observations (see above).

The Fleet, under the false impression that the position of the "Bismarck" would be reported by the supposed shadowing ships anyway, evidently did not expect that this radio telegram traffic would betray her and provide the enemy with a substitute for the lost contact. The radio telegram traffic, which lasted over half an hour, seemed to give the enemy ample opportunity to take an accurate bearing (Gibraltar and Iceland give a bearing angle of almost 90º for this position). The English fleet commander realized from this that he was already west of the "Bismarck", and ordered "King George" and "Rodney" to turn back to a north-easterly course, and then, in the afternoon, when he was within the "Bismarck" route, set a parallel course. After the radio bearings had established that "Bismarck" was on a south-easterly course on the morning of 25 May, no other conclusion could be drawn than that it was heading for western France. This resulted in the measures taken by the English fleet command.

In a speech that the Fleet Commander gave to the crew of his flagship on this Sunday, his birthday, he pointed out the seriousness of the situation. According to the testimony of survivors, his closing words, "victory or death," left a deep impression.

The critical situation of the ship prompted the Seekriegsleitung to inform the Fleet Commander through Group West that if the situation required it, calling at a northern Spanish port could be considered, and the Reichsmarschall [Hermann Göring] to issue the order to Fliegerführer Atlantik and Air Fleet 3:

-

"Aircraft are to protect the incoming battleship formation in the intended port as far as possible; flying towards them as far as possible.

Protection against destroyers and submarines.

Reichsmarschall".

-

1. Reconnaissance and combat operations are assigned to Fliegerführer Atlantik.

Advantages: operation unified command, uniform radio communication, rapid message transmission.

2. The air combat forces available are those of the Fliegerführer Atlantik (Group 606). In addition, further combat groups can be requested by Fliegerführer Atlantik, unlimited in size within the total forces of Air Fleet 3.

-

"Strong units are available for air operations during the arrival of the "Bismarck".

Combat units up to 14º West, reconnaissance up to 15º West, weak long-range units up to about 25º West.

Outpost patrol according to radio telegram 1313 with 5 boats in position 25 May forenoon, 2 more [boats] BE 67 and 63 not until 27 May in the morning.

For incoming escort, 3 destroyers.

Approaches off Brest and St. Nazaire are under intensified control. Heading into La Pallice also possible in case of emergency.

Early report of day and time is urgently required when crossing 10º West. Add quadrant if possible."

"Bismarck" continued its march on Sunday without any problems. The weather was deteriorating, with heavy seas, and the forecast predicted a further increase in wind and sea.

On the evening of May 25, the Seekriegsleitung was confident that the Fleet Commander had managed to shake off the shawdowing ships during the morning. This expectation opened up new, more favorable prospects. The Seekriegsleitung still hoped that the situation on board the "Bismarck" (effect of hits, fuel situation) would allow the Fleet Commander to move west or southwest into the open Atlantic. Only there did it seem possible to evade enemy air reconnaissance. It could be assumed with certainty that the enemy would try and do everything in its power to reestablish contact.

The Seekriegsleitung considered again suggesting to the Fleet Commander that he should move to the Atlantic. However, the idea was rejected because it did not seem right to influence the Fleet Commander in a particular direction. The Fleet Commander, who was informed of all enemy movements and measures detected, had the best overview of the situation on board and would be fully aware of the advantages and disadvantages of an evasive movement to the west or southwest (Seekriegsleitung war diary of 25 May).

26 May.

The morning of May 26th also passes without any particular events, with the sea and wind continuing to increase. The weather conditions in the Bay of Biscay, as Group West radios to the fleet, preclude the forward deployment of the security forces; therefore, only close air cover is possible for the time being. If the bad weather conditions in the Bay of Biscay continue, it will be impossible to pass the sandbar of St. Nazaire and to moor torpedo protection vessels there or in the roadstead of La Pallice. In this case, entering Brest will be necessary.

Then, just before noon, an unexpected and decisive turn of events occurred: "Bismarck" was sighted from the air and reported. At 1154, the Fleet Commander reported that an enemy wheeled aircraft was in contact in Quadrant BE 27, and almost at the same time the Intelligence service deciphered an enemy reconnaissance report that had been sent earlier: English aircraft X1AZ reported to 15 reconnaissance group: 1030 hours a battleship 150º, speed 20 knots, my position is (BE 1672 according to German quadrant reference).

The range of the aircraft (about 600 nautical miles) is surprising. According to the English reports, it was a Coastal Command aircraft, an American Catalina-type flying boat, which, operating at the very limit of its range, found the German battleship again, emerging from the low clouds. Under the effect of the anti-aircraft fire, it had to go back into the clouds and lost contact. Its sighting was, however, enough for the aircraft carrier "Ark Royal" (Capt. Maund) approaching from Gibraltar as part of Force H under Rear Admiral Sommerville to send its reconnaissance aircraft to the "Bismarck". Remanining outside the ship's anti-aircraft range, they kept in touch with it throught the day repeatedly rotating their patrols.

This meant that the Seekriegsleitung hopes of a solution along the lines of:

-

Moving to the southwest

Refueling from an escort tanker

Breakthrough through the Denmark Strait or south of Iceland to Norway or back home, had been dashed.

-

"Fuel situation urgent. When can I count on replenishment?"

The contact, which was only maintained by air, was in danger of being lost again in the approaching bad weather and in the darkness. The next morning, however, the "Bismarck" could reach the air cover of the French Atlantic coast. In this situation, Admiral Sommerville decided to make full use of his torpedo aircraft. After having sent the cruiser "Sheffield" (Capt. Larcom) ahead in the morning to establish contact and bring the torpedo squadrons from "Ark Royal" closer, he had the first group of torpedo planes launched in the afternoon, but they passed by the "Bismarck". Then, however, the "Sheffield" sighted the "Bismarck" at 1730 hours, but had to retreat at full speed behind an artificial smoke screen to evade heavy salvos. "U48" was sent against the "Sheffield" and the Fleet was informed of this at 1954 hours with:

-

"U48 in BF 71 has orders to operate at full speed against Sheffield."

According to statements from survivors, seven of the approximately 35 attacking English aircraft were shot down. In quick succession, the Fleet Commander reported:

-

"2105 quadrant BE 6192. Have sustained torpedo hit aft."

"2115 Ship no longer manoeuvrable."

"2115 torpedo hit amidships."

-

"2205 U-boats have orders to assemble in BE 6192."

At around 2000 hours in BE 5332, U556 (Kapitänleutnant Wohlfarth) made contact with a King George class battleship and the aircraft carrier "Ark Royal" (presumably the "Victorious"), which were passing the boat on a straight course unescorted at a short distance. By tragic coincidence, this particular boat, returning from a mission, was out of torpedoes. The boat lost contact shortly afterward in a rainstorm.

According to reconnaissance and radio observation reports, the following British forces were expected on the battlefield around "Bismarck" in the evening:

-

Battleships: King George V, Rodney, Renown, Prince of Wales (?), Ramillies (approaching),

Aircraft carriers: Ark Royal, possibly "Victorious",

Heavy cruisers: Norfolk, Dorsetshire,

Light cruisers: Sheffield, probably another,

Destroyers: 4th Destroyer Flotilla of the Tribal class.

-

2140 Ship unable to maneuver. We will fight to the last shell. Long live the Führer.

2325 Am surrounded by "Renown" and light forces.

-

2400 To the Führer of the German Reich, Adolf Hitler: We will fight to the end, believing in you, my Führer, and with rock-solid confidence in Germany's victory.

2400 Ship is weaponry-wise and mechanically fully intact; however, it cannot be steered with the engines.

0217 Submitting application for awarding the Knight’s Cross to Korvettenkapitän Schneider for the sinking of Hood."

0500 50% overcast, ceiling 600 meters. [Wind] from NW at force 7."

0625 Situation unchanged, wind force 8 to 9."

0710 Send U-boat for safe-keeping of war diary."

The Führer replied:

-

0153 I thank you in the name of the entire German people.

To the crew of the battleship "Bismarck":

All of Germany is with you. Whatever can still be done will be done. Your fulfillment of duty will strengthen our people in the fight for their existence.

Adolf Hitler.

His last request to save the war diary in order to make the important experiences of this operation useful for future warfare was attempted by sending U556, unfortunately without success.

The enemy was not unaware of the fateful turn caused by the Bismarck's inability to maneuver. Even in the dark, the four Tribal-class destroyers, "Cossack", "Maori", "Sikh", and "Zulu", which had previously been held back by the heavy seas, closed in and, during the course of the night, launched a series of torpedo attacks on "Bismarck" illuminated by flares. "Cossack" and "Maori" each claimed to have scored a hit. According to rescued men, which are disputed by the British side, the battleship's artillery sank one destroyer and set a second on fire. These nighttime skirmishes were detected and reported by our own submarines by the muzzle flashes; they were unable to engage in the heavy weather.

"Bismarck" itself no longer sent any reports about the fighting and its results during the night.

At 0300 hours, the Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe issued the order to call up all available long-range night fighters and night fighter divisions and to use them to protect the "Bismarck" against torpedo and bomb attacks.

At 0307 hours, the first wave, consisting of 27 combat aircraft and 6 reconnaissance aircraft, took off, reached the battlefield around 1000 hours, and attacked a light cruiser and an aircraft carrier but missed. The second wave, took off at 1537 hours with 45 combat aircraft, the third, took off at 2009 hours with 50 combat aircraft, and the fourth, took off at 0403 hours on May 28, but could only engage the retreating enemy and, according to British reports, sank the destroyer "Mashona" with bomb hits.

Admiral Tovey, the British fleet commander, had gathered the available heavy ships near the "Bismarck" during the night and, according to British sources, intended to launch the decisive artillery attack at daybreak. The German battleship's continued strong defensive readiness, demonstrated in the night battles, led him to abandon this plan, preferring to first further reduce the enemy's dangerous combat capability with torpedo aircraft. Only after an attack by a torpedo aircraft group launched from "Ark Royal" proved unsuccessful in the prevailing weather did "King George V" and "Rodney" launch their final assault. At over 160 hectometers [16,000 meters], they concentrated the fire of their 35.6 cm and 40.5 cm guns on the now almost motionless enemy. "Bismarck" initially returned fire accurately and effectively with its heavy and medium artillery, according to British sources. However, after a successful salvo in the forecastle knocked out the forward turrets and apparently also the fire control, the remaining guns continued to fire individually according to British observations but missed widely, and due to the significant reduction in range now sought by the British they were finally silenced. The heavy cruisers "Dorsetshire" and "Norfolk" also participated in this artillery engagement and claim to have scored over 300 hits with their 20.3 cm guns.

When artillery fire alone failed to achieve its intended goal of sinking the "Bismarck," Admiral Tovey dispatched the "Dorsetshire" to sink the silenced ship with torpedo fire. At close range, the cruiser hit the battleship's starboard side with two torpedoes without achieving any visible effect, according to the report of the "Dorsetshire's" torpedo officer. She then moved to the other side of the wreck and hit it with another torpedo, which brought about the end of the "Bismarck". With a powerful roll to starboard, the bows righted, and at 1101 hours, the ship sank with her colors flying.

The "Dorsetshire" took 85 survivors from the "Bismarck" on board and landed them in a British naval port; a sailor who died of his wounds was buried at sea with military honors during the crossing. The destroyer "Maori" rescued 25 men. No further rescue attempts were made by the British ships, or were aborted so abruptly for fear of submarine attacks that even those already clinging to the rescue ropes were not taken on board.

Three men were taken on board U74 at 1930 hours in BE 5330. The weather steamer "Sachsenwald" picked up two more survivors in BE 6150 during the night of 28/29 May. The rescue attempt by the Spanish cruiser "Canarias," which was gratefully accepted, was unsuccessful.

6. Operative Schlußbetrachtung.

Die operativen Folgerungen, die aus der "Bismarck"-Unternehmung gezogen werden müssen, sind zeitbedingt, d.h. sie müssen in Übereinstimmung gebracht werden mit der jeweiligen Gesamtkriegslage, der eigenen und der Feindlage.

Für die deutsche Seekriegführung mit überwasserstreitkräften war im Jahre 1941 der wichtigste Seekriegsschauplatz der Atlantische Ozean. Die im Winterhalbjahr 1940/41 glücklich und erfolgreich durchgefürten Handelskriegsoperationen der Schlachtschiffe und schweren Kreuzer bestärkten die Seekriegsleitung in der Zuversicht, durch einen fortlaufenden Ansatz von Überwasserstreitkräften im nördlichen und mittleren Atlantischen Ozean dem U-Boothandlskrieg eine wertvolle und wesentliche Unterstützung geben und den Gegner zu einer träfteverzehrenden Zersplitterung seiner Abwehrkräfte zwingen zu können. Dies Bestreben veranlaßte die Seekriegsleitung, die "Bismarck"-Operation zu befehlen, obwohl die Schlachtschiffe "Gneisenau" und "Schanrhorst" z. Z. und Schlachtschiff "Tirpitz" noch nicht einsatzbereit waren, und obwohl die kurzen Nächte der Sommermonate einen unbemerkten Durchbruch der "Bismarck"-Kampfgruppe in das Operationsgebiet erschweren mußten, ein Nachteil, der jedoch nach Ansicht der Seekriegsleitung zum Teil dadurch aufgehoben wurde, daß - wie es bei der "Bismarck"-Unternehmung auch tatsächlich der Fall war - während der Frühjahrsmonate in den hohen Breiten häufig unsichtiges Wetter angetroffen wird.

Die Seekriegsleitung war sich darüber klar, daß bei der Art ihrer Kriegführung jederzeit kleine Ursachen groß Wirkungen ausüben konnten und daß bei aller Umsicht der Führung von Land und See das Kriegsglück sich auch einmal wenden konnte.

Der Grundgedanke der Kriegführung mit Überwasserstreitkräften ist überraschung und ständiger Wechsel der Operationsbebiete, sie ist somit, auch wenn sie von Schlachtschiffen ausgeübt wird, eine echte Kreuzerkriegführung, bei der das Kämpfen mit gleichwertigen Gegnern stets nur Mittel zum Zweck sein darf. Die Hauptaufgabe der Marine ist und bleibt die Unterbrechung der Zufuhr nach England. An dieser Aufgabe müssen alle dafür geeigneten STreitkräfte teilnehmen. Nur in ihrer gegenseitigen Ergänzung und Wechselwirtung liegt wiederum die Entlastung für den anderen. Der kampf unserer U-Boote verlangt den Einsatz auch der Überwasserstreitkräfte entprechend ihren Möglichkeiten, für die Heimatkampfgruppe vornehmilich im Nordatlantik. Der Gegner fürchtet diese Art der Kampfführung besonders, da sie imstande ist, sein bisheriges Geleitzugsystem in Unordnung zu bringen und damit weitere erhebliche und untragbare Störungen seines Zufuhrverkehrs hervorzurufen.

Für die Kommenden Operationen ergeben sich aus der "Bismarck"-Unternehmung eine Reihe von Lehren:

1. Für den Anlauf der Operations muß verstärkter Wert auf das Moment der Überraschung gelegt werden, um dem Gegner die Kenntnis über den Anmarsch zu entziehen und ihm den Aufmarsch seiner Streitkräfte zu erschweren. Daher nicht mehr Anmarsch aus den deutschen Heimathäfen mit der Möglichkeit der Sichtung und Meldung durch Agenten schon von Belt und Sund aus, sondern Verlegen der Schiffe nach Drontheim schon wochenlang vor Beginn der Operation und Durchbruch bei geeigneter Wetterlage; günstiger, weil überraschender noch ist der Ausbruch aus einem Hafen der Atlantikküste.

2. Trotz des unglücklichen Verlaufs der "Bismarck"-Unternehmung ist die kleine bewegliche und leichter zu versorgende Kampfgruppe, selbst ein einzelnes Schlachtschiff oder Kreuzer, die gegebene Einheit für diese Art des Kreuzerkrieges. Sein Ziel ist nicht, zu einem Gefecht zu kommen, sondern vielmehr unbemerkt and die Seeverbindungen des Gegners heranzukommen.

Die Kampfgruppe soll nach Möglichkeit aus homogenen Einheiten bestehen in bezug auf Kampftraft, Geschwindigkeit und Seeausdauer.

3. Die Erschwerung der Brennstoffergänzung durch die feindlichen Flugzeugträger und Funkmeßgeräte erfordert eine andere Aufstellung unserer Tanker. Einmal dürfen diese Schiffe nicht ständig auf den Versorgungspunkten stehen, sondern müssen sich nach Möglichkeit wieder in ganz entlegene Gebiete absetzen, zum anderen ist die Mitgabe eines schnellen Troßschiffes erforderlich, das vermöge seiner hohen Marschgeschwindigkeit in der Lage ist, im Falle von Brennstoffnot schnell größere Räume überbrücken zu können.

4. Der Hochsommer mit seinem kurzen hellen Nächten ist vor allem für Operationen im Nordraum ungünstig. Seine Nachteile werden durch die Möglichkeit, in dieser Jahreszeit im hohen Norden häufig Nebel anzutreffen, nicht aufgewogen.

7. Schlußwort.

Seit dem Ausbruch und durch den Verlauf des deutsch-russischen krieges hat sich die seestrategische Lage weitgehend geändert. Die Versteifung des russischen Wiederstandes, die daraufhin einsetzenden umfangreichen Kriegsmaterialtransporte, die zu seiner Stützung aus den Vereinigten Staaten und England durch das Nordmeer nach der Murman-Küste und Archangelsk laufen, haben unseren Überwasserstreitkräften Einsatzmöglichkeiten gebrach, die bein einem geringeren Risiko von gleich großer Bedeutung für die Gesamtkriegslage sind wie die Handelskriegsführung im Atlantik. Auch erfordert die Gefahr einer feindlichen Landung an der nordskandinavischen Küste eine Konzentration starker Abwehr träfte im Raum des Nordmeers.

Andererseits hat, wie der Verlauf der "Bismarck"-Unternehmung und die rasch aufeinanderfolgende Versenkung der für die atlantische Kriegsführung unentbehrlichen Versorgungsschiffe erkennen lassen, die durch die Kühnheit unseres Vorgehens anfangs überraschte englische Seekriegsleitung ihre Gegenmaß nahmen inzwischen entscheidend verschärft, und durch die Kriegsteilnahme der U.S.A. und den Ausbau der amerikanischen Stützpunkte auf Grönland und Island haben sich sie operationen Bedingungen im Nordatlankik für uns weiter erheblich verschlechtert. Es muß ferner in Rechnung gestellt werden, daß die auf dem westlichen Kriegsschauplatz, zur Zeit bestehende seindliche Luftüberlegenbeit den Wert unserer an der französischen Küste gelegenen Stützpunkte als Ausweich bzw. Ausgangsbasis unserer Operationen wesentlich herabgesetzt hat.

Die drei Momente: Neubildung eines seestrategischen Schwerpunktes im Nordmeer, Festigung der feindlichen Abwehrstellung im Nordatlantik und starke Luftbedrohung der Haupteinsatzhäfen an der französischen Küste waren von maßgebendem Einflutz auf den Entschluß zur Ruckführung der schweren Schiffe in der Heimatbereich.

Bis auf weiteres muß daher - obwohl die Seekriegsleitung gewillt ist, bei einer späteren Veränderung der seestrategischen Lage grundsÇatzlich an dem Bestreben zur Fortführung weiträumiger Operationen unter bewußter Inkaufnahme des Risikos festzuhalten - dem Einsatz unserer Überwasserstreitkrafte im Nordmeer unter bewußtem Verzicht auf die Kriegführung im Atlantik der Vorrang gegeben werden.

Copyright © 1998-2024 KBismarck.com