OPERATION RHEINÜBUNG

By José M. Rico

The Bismarck moored to Seebahnhof pier in Gotenhafen in May 1941, shortly before Operation Rheinübung.

The Bismarck moored to Seebahnhof pier in Gotenhafen in May 1941, shortly before Operation Rheinübung.

A New Atlantic Sortie.

Following the success achieved by the surface ships in the Atlantic during the winter of 1940-1941, the German Naval High Command decided to launch a much more ambitious operation. The idea was to send a powerful battle group comprised of the battleships Bismarck, Tirpitz, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau into the Atlantic to attack Allied merchant shipping. The latter two battleships were in Brest, in occupied France, since 22 March. They had just completed a successful campaign of two months in the North Atlantic under the command of the Fleet Chief, Admiral Günther Lütjens, in which they sank or captured 22 ships with a total tonnage of 116,000 tons. Unfortunately, the Scharnhorst had to enter dry dock in order to undergo machinery repairs and would be unavailable at least until June. In the Baltic, the Bismarck had almost finished her trials and would soon be ready for her first war cruise. However, the Tirpitz, which had only recently been commissioned on 25 February, had not yet completed trials, and it was unlikely that she would be available in the spring.

On 2 April, the same day the Bismarck received her last two Arado 196 aircraft, the Naval Warfare Command (Seekriegsleitung) outlined the strategy to follow in its operational directive (B.Nr. 1. Skl. I Op. 410/41 Gkdos Chefs.1). With the Scharnhorst in dry dock and the Tirpitz not ready for action yet, it was decided that the Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen would be sent into the North Atlantic in late April under the command of the Fleet Chief. The Gneisenau would later sail from Brest to join them. The mission of the German ships was to attack convoys operating in the Atlantic north of the Equator. However, because of the success of the German warships in recent months, the Allied convoys had improved their protection and were now strongly escorted by either battleships or cruisers. So, it would be Bismarck’s duty to engage the escorts while the other ships attacked the merchant vessels virtually unopposed.

The British Admiralty was very concerned and had serious indications that the Germans were planning a large surface operation in the Atlantic. The British knew of the presence of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in Brest and the danger they posed should they sortie in conjunction with Bismarck. Therefore, they decided to immobilize these two battleships through air raids. On 6 April, a Coastal Command Beaufort plane (Lieutenant Kenneth Campbell) of the 22º Squadron scored a torpedo hit on Gneisenau's starboard side between sections IV and V. Although the British aircraft was shot down by the land-based anti-aircraft batteries, the Gneisenau was damaged and had to enter dry dock for repairs. A few days later, during the night of 10/11 April, the battleship was hit again. This time by four 500lb SAP bombs dropped by the RAF which killed 72 men and forced to lengthen the repair work for months. As a result of these attacks, the German force was reduced to Bismarck and Prinz Eugen, which would be the only heavy warships available to participate in attacks on enemy merchant shipping that spring.

There were more than enough reasons to cancel the operation until a larger force could be assembled. By the autumn, the Tirpitz would be worked up and the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in Brest would be ready again. Also the short spring nights made it more difficult for the German ships to reach the Atlantic undetected. Despite this, the idea to send the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen to the Atlantic in the spring remained a viable one. The United Kingdom was in a critical situation for supplies, and five months of "relative calm" at sea would have only strengthened her position. There was also the increasing fear that the United States would join the war, resulting in greater detection capabilities, and thus, reducing to a considerable extent the movements of the German fleet. The Commander-in-Chief of the Kriegsmarine, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, thought it more important to utilise Bismarck's potential and keep up the pressure on the British supply lines, and, therefore, he decided to go on with the operation. The most important factor was that the two German ships could reach the Atlantic unobserved. From there, they could get lost in the immensity of the ocean and attack enemy convoys at will.

In the meantime, Admiral Lütjens had met the Commander in Chief, U-boats, Vizeadmiral Karl Dönitz, in Paris on 8 April. Both Admirals knew each other well as they had worked together on several occasions before the war. At that conference they outlined the U-boat support that was to be given to the Bismarck. It was agreed that the U-boats would carry on as usual in their normal positions, but if any opportunity arose for a combined action with Bismarck, it would be fully exploited. A U-boat liaison officer was therefore assigned to the Bismarck.

On 22 April, Admiral Lütjens established the details of the operation now code-named Rheinübung (Rhine Exercise). The departure of the German ships was imminent, but on 23 April the Prinz Eugen was damaged by a magnetic mine while en route to Kiel. This required repair work which delayed the operation for two weeks. Three days later, on 26 April, Lütjens and Raeder met in Berlin to discuss the situation. The Fleet Chief suggested to Raeder the possibility of postponing the operation until the Scharnhorst and/or Tirpitz would be ready. The Grand Admiral, however, thought it was imperative to resume the Battle of the Atlantic as soon as possible and ordered the operation to go forward.

Meanwhile, aboard the Bismarck, everything was reaching a level of maximum readiness. In late April, two new 2 cm Flak C/38 quadruple mounts were installed on both sides of the foremast above the searchlight platform. On 28 April, Captain Lindemann informed the Naval High Command (OKM), Group North, Group West, and the Fleet Command that the Bismarck was personnel-wise and materiel-wise fully ready for action, and provisioned for three months.2 He noted in the ship's war diary:

"The first phase in the ship’s life since the commissioning on 24 August 1940, is successfully completed. The goal was reached after eight months, being over the target date by only fourteen days; although the original intention (Easter) was missed by a forced waiting period in Hamburg (24.1–6.3.1941) of six weeks, due to the closing of the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and by ice jams.

The crew can be proud of this accomplishment. It was accomplished, because there was an overall common desire to engage the enemy as soon as possible. I, therefore, had no qualms to make extremely high demands on them for a prolonged period of time, and because the ship and his equipment had been totally spared, despite of hard use and very Spartan lay-up time, from extensive breakdowns and damage.

The state of training that has been reached, compares favourably with that of a capital ship’s readiness for a full [scale] battle inspection in the good years of peacetime. Although the crew, with few exceptions, completely lacks real combat experience, I have the calm feeling that all forthcoming combat demands will be readily dealt with. This feeling is strengthened by the fact that the combat value of this ship, by virtue of the achieved state of training, awakens great confidence in every man so that - for the first time in a long time – we can feel at least equal against any opponent.

The delay of our deployment, whose approximate time could not be kept hidden from the crew, is a tough disappointment for all involved.

I will use the waiting period in the previous manner, for the further perfection of training, but also to provide somewhat more rest for the crew. Furthermore, I intend to devote more time to division duties and the outer maintenance of the ship, since both of these duties necessarily had to take on very minor role. In addition, I will replenish weekly the expended stores of the three months requisition requirements."

On 5 May, Hitler visited Gotenhafen to inspect both the Bismarck anchored in the roadstead, and the Tirpitz at the pier in the harbour. Consequently, the Führer's personal pennant as well as the flag of the Chief of Fleet, were hoisted aboard. Raeder was absent, and Lütjens received Hitler, but he didn't inform him about the upcoming sortie of his ships.

Early on 13 May, Admiral Lütjens and the Fleet Staff embarked in the Bismarck and then the ship spent the afternoon in the Bay of Danzig conducting refuelling exercises with the Prinz Eugen before anchoring off Gotenhafen in the evening. On the next day, during the course of other exercises, this time with the light cruiser Leipzig, Bismarck's 12-ton portside crane broke down. Since this affected the deployment of the ship's aircraft and boats, the departure of the Bismarck was once again delayed in order to repair the crane. Finally on 16 May, Lütjens informed Group North that the ships were ready, and the date for the beginning of Operation Rheinübung was established for 18 May.

The heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen being refuelled by the Bismarck during a training exercise in the Baltic Sea. Unlike other navies that executed this manoeuvre side by side, the Kriegsmarine did so placing both ships in line. This photo was possibly taken on 13 May 1941.

Bismarck's Departure.

At 1000 on the morning of 18 May 1941 in Gotenhafen, Admiral Lütjens accompanied by his personal aide went aboard the Prinz Eugen and inspected her crew. Afterwards, a conference was held on board the Bismarck, where the Admiral briefed the operative plan to the two ships' commanders, Captains Ernst Lindemann and Helmuth Brinkmann. It was decided that if the weather proved favourable, they would not stop in the Korsfjord (today Krossfjord). They would, instead, sail north to refuel from the Weissenburg before cruising into the Denmark Strait between Iceland and Greenland.3

At noon, the Bismarck left the berth under the tunes of Muß i' denn played by the fleet band, and then she anchored in Gotenhafen's roadstead to take on supplies and fuel. Operation Rheinübung had begun. While refuelling in the roadstead, one of the fuel-oil hoses broke and Bismarck could not be refuelled to her full capacity. It was nothing significant, although the battleship was loaded with approximately 200 tons less of fuel. Shortly after 2100, the Prinz Eugen weighed anchor. Bismarck followed suit at 0200 in the early morning of 19 May. Both ships sailed independently until they joined together off Rügen Island at 1125 hours on 19 May. It was then that Captain Lindemann informed Bismarck's crew by loudspeaker that they were going into the North Atlantic to attack British shipping for a period of several months. After this, the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen sailed west escorted by the destroyers Z23 (Fregattenkapitän Friedrich Böhme) and Z16 Friedrich Eckoldt (Fregattenkapitän Alfred Schemmel). At 2230, the destroyer Z10 Hans Lody (Fregattenkapitän Werner Pfeiffer) with the Chief of the 6th Flotilla (Fregattenkapitän Alfred Schulze-Hinrichs) on board, joined the formation too. During the night of 19/20 May the German ships passed through the Great Belt, which remained closed to merchant ships, and then reached the Kattegat in the morning of 20 May.

On 20 May, while in the Kattegat, the German battle group was sighted by numerous Danish and Swedish fishing boats. The weather was clear, and at 1300, the German ships were sighted by the Swedish cruiser Gotland (Captain Knut G. Ågren) which reported the sighting to Stockholm. Lütjens assumed this ship would report his position and immediately radioed this incident to Group North. The Swedish had reported the sighting and then it was leaked to the British Naval Attaché, Captain Henry W. Denham. Later in the day, from the British embassy in Stockholm, Denham transmitted to the Admiralty in London:

"Kattegat, today 20 May. At 1500, two large warships, escorted by three destroyers, five ships and ten or twelve planes, passed Marstrand to the northeast. 2058/20."Meanwhile, at 1330, the 5th Minesweeping Flotilla (Korvettenkapitän Rudolf Lell) joined the battle group temporarily to help the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen pass through the German minefields that blocked the entrance to the Kattegat off Skagen. Three mines were detonated, and at 1613 the minesweepers were dismissed. At dusk on 20 May, the German ships were already getting out of the Skagerrak near Kristiansand. They were then sighted from the coast by Viggo Axelssen, of the Norwegian resistance, who duly reported the sighting to the British in London via Gunvald Tomstad's secret unregistered personal transmitter at Flekkefjord. During the night of 20/21 May the Germans headed north.

The Bismarck during her voyage to Norway seen from a minesweeper of the 5th Flotilla on 20 May 1941.

Early on 21 May, the British Admiralty received the sighting report from Denham, and aircraft were instructed to be on the alert for the German force. At about 0900 hours, the German squadron entered the Korsfjord south of Bergen with clear weather. Admiral Lütjens initially wanted to continue to the north without stopping in Norway, but because of the clear weather he decided to enter the Korsfjord and continue the voyage that night under cover of darkness. Pilots were taken aboard the German ships, and at noon, the Bismarck anchored in the Grimstadfjord at 250-500 metres off the nearest shore. The Prinz Eugen headed north with the three destroyers and anchored in Kalvanes Bay. As a measure of precaution two merchant ships were laid along both sides of Prinz Eugen as torpedo shields. The voyage from Gotenhafen to Bergen covered approximately 950 miles.

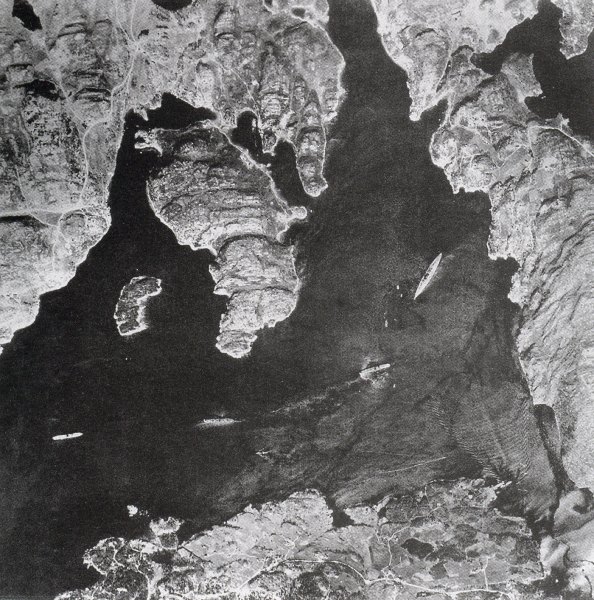

The Bismarck in the Grimstadfjord, Norway, as seen from the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen in the morning of 21 May 1941.

Meanwhile, at 1100 on 21 May, the British Coastal Command had dispatched two Spitfires from Scotland to search the Norwegian coastline and look for the German ships. At 1315, one of them, piloted by Flying Officer Michael F. Suckling, successfully sighted and photographed the German ships near Bergen from an altitude of 8,000 metres (26,200 feet), and then returned to Scotland where it landed at Wick Airfield at about 1415. The sighting of the German battle group by the Swedish cruiser Gotland in the Kattegat as well as by Norwegian resistance operatives the previous day, had proven very unfortunate for the Germans. If the German group would have passed through the Kiel Canal instead, this may have possibly prevented such immediate sightings, and thus the Coastal Command sending the reconnaissance Spitfires. Unfortunately, it took two full days to transit the canal and it was not considered a viable option by the German command.

During their brief stay anchored in Norway, the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen painted over their striped camouflage paint with outboard grey.

In addition, the Prinz Eugen with less than 2,500 mt of fuel oil left in her tanks refuelled from tanker Wollin.

The Bismarck did not refuel and this would later prove to be a mistake.

It seems that refuelling the Bismarck was not scheduled, and that Prinz Eugen was refuelled only because she absolutely had to be due to her shorter endurance.

By 1700, the Prinz Eugen completed refuelling, and at 1930, the German ships weighted anchor.

At this time, Bismarck's intelligence team received a message from Germany, in which, based on an intercepted radio message, British aircraft had been instructed to be on the alert for two battleships and three destroyers proceeding on a northerly course.

Around 2000, just before nightfall, the five German ships left the Norwegian fiords, and after separating from the coastline, set a course of 0º at 2340, due north.

During their brief stay anchored in Norway, the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen painted over their striped camouflage paint with outboard grey.

In addition, the Prinz Eugen with less than 2,500 mt of fuel oil left in her tanks refuelled from tanker Wollin.

The Bismarck did not refuel and this would later prove to be a mistake.

It seems that refuelling the Bismarck was not scheduled, and that Prinz Eugen was refuelled only because she absolutely had to be due to her shorter endurance.

By 1700, the Prinz Eugen completed refuelling, and at 1930, the German ships weighted anchor.

At this time, Bismarck's intelligence team received a message from Germany, in which, based on an intercepted radio message, British aircraft had been instructed to be on the alert for two battleships and three destroyers proceeding on a northerly course.

Around 2000, just before nightfall, the five German ships left the Norwegian fiords, and after separating from the coastline, set a course of 0º at 2340, due north.

Upon receipt of the first sighting reports, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Home Fleet, Admiral Sir John Cronyn Tovey, immediately began to consider the possible intentions of the German warships. He ordered the heavy cruisers Suffolk and Norfolk, both under the command of Rear-Admiral William Frederick Wake-Walker, to patrol the Denmark Strait. Later in the afternoon, the photos taken by the Spitfire arrived, thus positively identifying one Bismarck class battleship and one Hipper class cruiser in Bergen. Therefore, shortly before midnight on 21 May, the battlecruiser Hood flying the flag of Vice-Admiral Lancelot Ernest Holland, the battleship Prince of Wales, and the destroyers Achates, Antelope, Anthony, Echo, Electra, and Icarus, left Scapa Flow for Hvalfjord in Iceland. Their mission to cover the access points south and east of Iceland.

Photograph taken by the British Spitfire (Suckling) at 1315 hours on 21 May 1941. The Bismarck can be seen to the right anchored in the Grimstadfjord near Bergen, Norway, with three merchant ships. Position 60º 19' 49" North, 05º 14' 48" East. The steamers would serve as torpedo shields in case of enemy attack. Unlike many other publications, this photo is shown here in its correct orientation, North up.

To the Denmark Strait.

On 22 May, the weather worsened. During the night, the German battle group headed North, with the three destroyers in the lead and the Prinz Eugen closing the formation. At 0420, the destroyers were dismissed and headed east to Trondheim, while the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen maintained their northward course at 24 knots. At 1237 there was a submarine and air alarm, and the German ships zig-zagged for about half an hour. When the alarm ended, the tops of the main and secondary turrets were painted over, and the swastikas on the decks were covered with canvas, as they could help enemy aircraft to identify the German ships. Afterwards, the group set a northwest course to the Denmark Strait. It was cloudy the entire day and the fog was so thick that the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen had to switch on their searchlights from time to time in order to maintain contact and keep position. The weather conditions were therefore very favourable for the German ships to pass through the Denmark Strait and reach the Atlantic unnoticed.

The Prinz Eugen follows Bismarck in the fog with the help of a searchlight. 22 May 1941.

Back in Germany, Admiral Raeder finally informed Hitler at the Berghof that the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen were en route to the Atlantic in order to wage war against merchant shipping. Hitler was anxious and expressed his doubts and fears, but Raeder succeeded in convincing him to continue with the operation.

Meanwhile, at 2000 on 22 May, Admiral Tovey received news that the German warships had departed Norway. He then left Scapa Flow with the battleship King George V, the aircraft carrier Victorious, the light cruisers Kenya, Galatea, Aurora, Neptune, Hermione, and the destroyers Active, Inglefield, Intrepid, Lance, Punjabi and Windsor. The battlecruiser Repulse, sailing from the Clyde, was to join them later the next morning. That night of 22/23 May, after receiving the report, Winston Churchill cabled to president Franklin D. Roosevelt:

"Yesterday, twenty-first, Bismarck, Prinz Eugen and eight merchant ships located in Bergen. Low clouds prevented air attack. Tonight [we discovered] they have sailed. We have reason to believe that a formidable Atlantic raid is intended. Should we fail to catch them going out your Navy should surely be able to mark them down for us. King George V, Prince of Wales, Hood, Repulse and aircraft carrier Victorious, with auxiliary vessels will be on their track. Give us the news and we will finish the job."4On 23 May the weather remained the same. At 1300 hours the clocks in the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen were set back by one hour on Central European Time.5 That afternoon, at 1420, the German ships set a course of 270º and began approaching the narrow passage between the Greenland ice-pack and the British minefields laid in the area. Therefore, at 1730, the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen turned their magnetic self-protection systems on. At 1811, the Germans sighted ships to starboard, but soon realised they were actually icebergs which were common in those latitudes. A few minutes later, the battle group reached the ice limit, and set a course of 240º. Suddenly, at 1922, the alarm sounded aboard the Bismarck when the heavy cruiser Suffolk was briefly sighted in the mist at a distance of seven miles. The Germans, however, were unable to engage because the cruiser quickly disappeared into the fog. The Suffolk had in fact sighted the enemy as well before retreating and sent the proper report without delay: "One battleship, one cruiser in sight at 20º. Distance seven miles, course 240º."6 About an hour later, at 2030, the Germans sighted the heavy cruiser Norfolk, and this time the Bismarck opened fire immediately. She fired five salvos, three of which straddled the Royal Navy ship throwing some splinters on board. The Norfolk was not hit by any direct impact, but had to turn hard to starboard, launch a smoke screen, and retire into the fog. Both British cruisers then took up positions astern of the German ships; the Suffolk (equipped with a new Type 284 radar) on the starboard quarter, and the Norfolk (with an older Type 286M radar) on the port quarter. They limited themselves to keep R. D/F (radio direction-finding) contact and report the position of the German squadron until more powerful British ships could engage.

On board the Bismarck the forward radar instrument (FuMO 23) had been disabled by the blast of her forward turrets. Because of this, Admiral Lütjens ordered his ships to change stations, and the Prinz Eugen with her radar sets (FuMO 27) intact took the lead. Bismarck's powerful artillery would serve to keep the British cruisers from coming any closer. This change would produce great confusion on the British the next morning.

After being sighted by cruisers Suffolk and Norfolk, Lütjens could have then turned around and head for the Norwegian Sea in order to refuel from tanker Weissenburg. He had already done this earlier that year when in command of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau his force was detected by the British cruiser Naiad in the Faeroes-Iceland gap. An early retreat at this point would have forced the four British capital ships (Hood, Prince of Wales, King George V and Repulse) that had already put to sea, to go back to Scapa Flow with a considerable expenditure of fuel. This time however, Lütjens continued towards the Atlantic with the hope of shaking off the British cruisers at night. The weather conditions in the Denmark Strait were favourable to do so. When Lütjens decided to press on, it is probably because he believed that the heavy units of the Home Fleet were too far away to intercept him, and that they may even still be in Scapa Flow. The German reconnaissance reports seemed to confirm this, although the truth is that Vice-Admiral Holland's force was already approaching the area at high speed. Another thing Lütjens did not count on was the effective use of British radars. Towards 2200 hours, the Bismarck reversed her course trying to catch the Suffolk, but the British cruiser withdrew maintaining the distance. Therefore, the Bismarck returned to the formation behind the Prinz Eugen.

As soon as the first sighting reports arrived, and despite the unfavourable weather, the British decided to sent out reconnaissance planes from Iceland to patrol the Denmark Strait and locate the German force. At 2225 hours, Short Sunderland Z/201 (Flight-Lieutenant R. J. Vaughn) took off from Reykjavik. This flying boat was followed by Lockheed Hudson L/269 (Flight-Lieutenant Devitt) that took off from Kaldaðarnes airfield at 2318 hours.7

Footnotes:

1. Report No. 1, Office of Naval Operations 410/1941 Secret Command Subject, For the Attention of the Chief.

2. Group North was the German Naval command station based in Wilhelmshaven. It was at that time under the command of Generaladmiral Rolf Carls. Group West was based in Paris under the command of Generaladmiral Alfred Saalwächter.

3. Iceland was occupied by the British on 10 May 1940, following the German invasion of Denmark. By May 1941, as much as 25,000 British troops were stationed in the island.

4. WSC to FDR, May 23 (FDR microfilm I/0323). Also see PRO ADM 205/10.

5. All times are given in German Summer Time which was the same as the British Double Summer Time (both one hour ahead of Central European Time and two hours ahead of Greenwich).

6. Able Seaman Alfred Newall aboard Suffolk was the first man to sight the Bismarck in the Denmark Strait.

7. L/269 landed back at 0405 hours having seen nothing. Lockheed Hudson G/269 (Flying Officer A.J. Pinhorn) took off at 0400 hours on the 24th, and although it later watched the battle at the Denmark Strait, was not able to identify any of the ships.

Copyright © 1998-2024 KBismarck.com